Becoming communal archiveThis page serves as documentation of a practice-based research performance I created for the Performance Lab module as part of my MA. The resources we had were limited and we were required to co-curate a wide range of individual and group performance showings, thus limiting our performances further. I include images and spoken words from my live performance, before and after. However, the majority of my writing here is from a portfolio documenting and explaining my choices for my research. My performance practice results from devising this research question as my basis:

When the affective and theatrical boundaries of performer and audience are collapsed, how is this relationship negotiated through the production of an embodied, collaborative archive?

Written and spoken provocation to the audience:

DESTROY THE IDEA THAT THE PERFORMER PASSES DOWN MEANINGFUL ART TO THEIR PASSIVE AUDIENCE, WHO SITS LOOKING IN AWE AT THEIR VIRTUOSITY.

THE AUDIENCE IS A COLLABORATOR, AN EQUAL IN THE MEANING-MAKING PROCESS. COMMUNAL ARCHIVES CANNOT EXIST WITHOUT COLLABORATION.

GET UP, OUT OF YOUR SEATS AND COMFORTABLE SPECTATORIAL ISOLATION. PICK UP A PEN AND DRAW ON ME.

MY SKIN, MY BODY, IS YOUR ARTISTIC MEDIUM NOW. WRITE A FEELING, A SECRET, A STORY ON ME.

YOU HAVE 5 MINUTES TO TURN ME INTO A REPRESENTATION AND DOCUMENT OF YOU.

WHILE YOU USE MY BODY TO DOCUMENT YOURSELVES, I WILL MANOEUVRE MY BODY TO SHARE WITH YOU SOMETHING ABOUT ME.

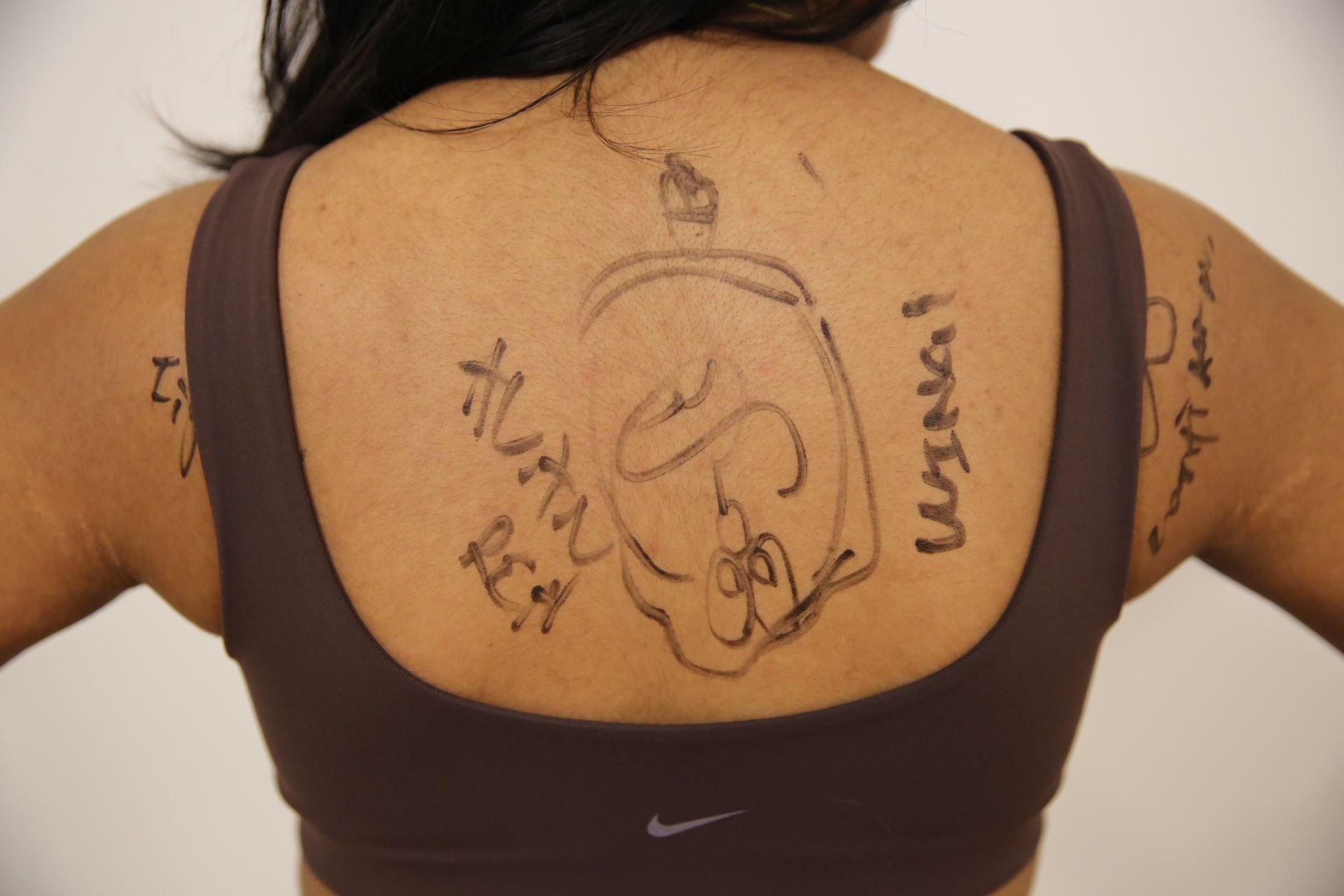

In March 2024, I performed my practice-based research in our Performance Lab showings at the Anatomy Museum, King’s College London, exploring the relationship between the audience and performer in creating an embodied collaborative archive. My practice involved inviting the audience to use pens to write on my body while I stretched and moved using yoga poses. My performance and research question were almost entirely dependent on the live event: I could not have completed my performance without participation from the audience. As a result, I had very little control over the responses, leading to some comical and perhaps inappropriate writings on my body, such as ‘I love Mambo No.5’, and the Chanel logo. Yet, this was the requirement of my performance: it was up to my audience to decide how they would interact. I included a provocation in the programme: ‘DESTROY THE IDEA THAT THE PERFORMER PASSES DOWN MEANINGFUL ART TO THEIR PASSIVE AUDIENCE, WHO SITS LOOKING IN AWE AT THEIR VIRTUOSITY.’ I reject masculinist, authoritative ideals of the artist, inspired by feminist endurance art, particularly Yoko Ono’s Cut Piece in 1964 and Marina Abramović’s Rhythm 0 in 1974. I removed the boundaries of performer and audience, especially prompted by Ono’s description of Cut Piece: ‘It was a form of giving, giving and taking…I wanted people to take whatever they wanted’. My performance responds to my racialized and gendered marginalisation to objecthood, becoming an embodied archive of the audience. In this critical reflection, I examine the ways in which my performance explored this research question on the audience/performer relationship within collaborative documentation. I discuss the role of objectification, embodiment and archivisation in order to demonstrate the theoretical and methodological basis of my performance research.

Firstly, I examine the role of endurance within my performance. Although my performance was limited to five minutes, even this invoked my physical endurance. I stretched and manipulated my body in ways that allowed the audience to write on my skin, while also disrupting their interaction. My performance demonstrated ‘physical culture’ and cultivation of muscles and flexibility, inspired by Broderick Chow’s The Dynamic Tensions Physical Culture Show. I displayed my physical capabilities, putting my body under pressure in front of an audience. In Performing Endurance, Lara Shalson proposes that ‘endurance is both something done and something undergone. We perform the act of endurance, but we are also made to endure by circumstances that exceed our command’. Shalson highlights how the performer is ‘made to endure’, implying the audience’s role in putting the performer’s body under duress. The relationship between the performer displaying endurance and the audience holding the performer accountable to it implicates an objectifying gaze.

As a result, I explored the objectification of my body in relation to the audience. Shalson writes:

objecthood describes the condition of existing as a body whose capacity to be acted upon precedes any ability to act of one’s own volition, and whose dependence upon others exceeds any capacity to make oneself known.

Whilst I situated my body as written document, inviting the audience to draw or write on my skin, my practice of ‘objecthood’ could not function without their participation, depending upon this relationality. I declared: ‘MY SKIN, MY BODY, IS YOUR ARTISTIC MEDIUM NOW. WRITE A FEELING, A SECRET, A STORY ON ME,’ asserting this objectifying relationship. This provocation was inspired by Abramović’s Rhythm 0, where she invited the audience to use 72 objects from a table on her. She wrote: ‘I am the object’, presenting herself as another object to be “used”. By foregrounding my skin and body, my Brown, feminine-presenting body bears the burden of this objectification, through my gendered and racialized subjectivity. Shalson argues that ‘coming to terms with objecthood and the ambivalence that it inspires has the potential to be an ethical act’. I endure objectfication in order to interrogate the ethics and politics of gendered and racialized bodies being relegated to material. Through writing on my body, my performance of objecthood could not have manifested without this relationship between audience and performer.

My research question is preoccupied with the idea of using my body as a collaborative archive. Chow’s interest in the ‘cultivation of the body’ through exercise implicates the cultures and histories that the body experiences and remembers. Chow’s understanding of physical culture links to André Lepecki’s proposal: ‘The body is archive and archive a body’. Similar to Diana Taylor’s writing on how ‘embodied and performed acts generate, record, and transmit knowledge’, Lepecki’s assertion expands past Taylor’s differentiation between the ‘archive’ and ‘repertoire’, by suggesting that the body is an “archive” of dance.

I performed endurance and physical culture through yoga stretches, engaging with the form’s nationalist histories. Yoga originates from India, before the formalisation of Hinduism as a religion, but is currently associated with Brahminical hindutva (Hinduness) and religio-nationalism. Yet, yoga has spread within Western societies as a physical culture that enacts peace and healing, with the largest user demographic in the US and UK being white women. The globalisation of yoga has elucidated the potential for Indian nationalists, specifically the far-right wing BJP and Prime Minister Narendra Modi, to position India internationally as culturally significant whilst occluding extreme casteist and Islamophobic violence for which they are responsible. Shameem Black notes the positioning of yoga as ‘the property of the nation… used to project India’s attractiveness as a destination for foreign investment’, while Anusha Lakshmi highlights how ‘Modi has capitalized on yoga’s associations with harmony and flexibility to distract from his administration’s divisiveness and authoritarianism’. India’s right-wing advocates for the global spread of yoga, such as International Day of Yoga, profiting from its associations with peacefulness to obscure capitalistic and racial hegemonies. Under British rule, yoga was seen as an anticolonial mode of physical cultivation in India to fight back against imperial control. Thus, BJP appropriates discourses of decolonization for the purposes of maintaining contemporary caste, religious and ethnic oppressions. Swati Arora suggests that if Performance Studies is to decolonise its histories of colonial violence, this must involve critiques of non-Western racialisations, like caste. I undertake decolonising critiques that encompass caste in my performance, by disrupting the act of surya namaskar (sun salutations), refusing to reify contemporary hindutva connotations of the movement in India. I did not strictly follow the codes of yoga, instead interspersing non-yogic stretches. I moved in sync with my body’s wants, desires, aches, and I interrupted yoga’s strictures to perform in accordance with my ethics and politics of anti-coloniality. Therefore, my performance renegotiated embodied archives of yoga by mishandling these histories.

My performance also engaged with the archive through my embodiment of written document. While Taylor’s seminal work on the archive and repertoire does touch upon how ‘materials from the archive shape embodied practice in innumerable ways’, she obscures how embodiment is always present in modes of archivization. During my provocation to the audience, I stated: ‘YOU HAVE 5 MINUTES TO TURN ME INTO A REPRESENTATION AND DOCUMENT OF YOU.’ My performance interrogates this relationship between embodiment and document by turning my skin into a medium for audience members to write upon. Yet, the audience simultaneously transforms into archivists through the embodied act of getting out of their seats to write on me. Claire Bishop suggests of participatory performance that ‘the audience, previously conceived as a “viewer” or “beholder”, is now repositioned as a co-producer or participant’. As a result, my invitation to the audience indicates their role as ‘co-producer’ and embodied archivists within my performance.

My choice of costuming included a brown sports bra and black shorts; however, this decision to expose the rest of my body meant that my Brown skin, tattoos, hair and body hair all became part of this costume. This vulnerability and exposure of my body invokes a sense of the intimate becoming public through its visibility. Similarly, by provoking the audience to write a ‘secret, feeling or story’ on me, the participant shares something private with me and the rest of the audience. My partner in the audience wrote ‘Wings’ on my back, as he wished for the ability to fly back to New Zealand to see his family whenever he missed them, highlighting this affective, archival collaboration. Our pre-existing bond further nuances the audience/performer relationship, exposing personal relationships for strangers to view. Shalson discusses of audience participation in Ono’s Cut Piece:

…they had to negotiate [Ono’s objecthood] in relation to each other and under the watchful gaze of other audience members, making clear that interpersonal relations are always embedded within broader group structures and dynamics.

In Cut Piece, the audience members can see what parts of Ono’s clothing the others have cut away, shouting at those who they believe are participating inappropriately. During my performance, audience members could see what others had written on parts of my body that were exposed during each movement. In fact, many responses could only be seen when approaching my body to write. Thus, my performance as document only functioned through embodied audience participation. My performance explored the relationship of audience to performer, and other audience members, by complicating the binary of archivization and embodiment.

I further complicated the division between archive and performance by choosing to document the responses written on my body with photographs. There were multiple reasons for this: I could not see what was written, apart from the few words on my forearms and legs, I wanted to understand how the audience responded to my performance, and I needed to write about my performance for this assessment (!). Inviting audience members to write on me, then documenting and holding their live responses accountable, elicits ethical questions about labour, vulnerability and intimacy. The relationship between audience and performer transformed me into an object, exposing private bodily secrets. Yet perhaps my engagement with documentation positions the audience too as exposed objects of public visibility.

My performance interrogates the relationship between performer and audience through the production of my body as a collaborative archive, problematising the distinctions between archive and embodiment. My preoccupation with this question is centred upon the colonial logics of the archive, which dictates that embodied acts and performance “disappear” after the live event. However, the role of time in my performance is crucial to my investigation of embodied archives. Whilst the argument for ephemerality maintains that the performance cannot exceed beyond the live event, my performance unsettles this. Before the live performance, I practised writing on myself, wearing and feeling pen on skin as preliminary research. Then after the showing, the writing on my skin served as a documentary reminder, whilst the aches and relief of stress in my muscles indicated the after-effects and -affects of my embodied endurance. My body remembers what it felt during the performance, continuing from the live event into the future as a medium of remembering. Thus, my practice-based research about the relationship between performer and audience within the creation of a communal archive raises further questions about temporality, durationality and endurance in performance. My performance research has incited further study and practical experimentation that could only have been achieved through this methodology.

Practising embodied documentation